Should immunotherapy infusion centers close after lunch?

Socioeconomic status, subtype, smoking, and sex may be driving the signal instead

Patients with cancer who receive immunotherapy earlier in the day have better outcomes. The first randomized trial to determine the effect of time-of-day of immunochemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was presented at ASCO 2025 (Zhang et al 2025, Abstract ASCO 2025; X thread of some of the slides were posted) where they demonstrated a median overall survival gain of at least 15 months if patients received therapy before 3 pm. Most cancer therapies extend overall survival by a few months if at all. So, if time-of-day makes a multiple fold-difference in survival relative to most new drugs, it raises two important questions: 1) Should infusion centers close down after lunch?, 2) If a patient gets scheduled for an afternoon slot, should the patient refuse it and only accept morning slots?

The clinical benefit observed in this trial is backed up by biological data supporting the impact circadian rhythms have on response to immunotherapy. In this article, however, we will step through the data presented from this randomized trial and explore reasons it may not be a true benefit that we observe.

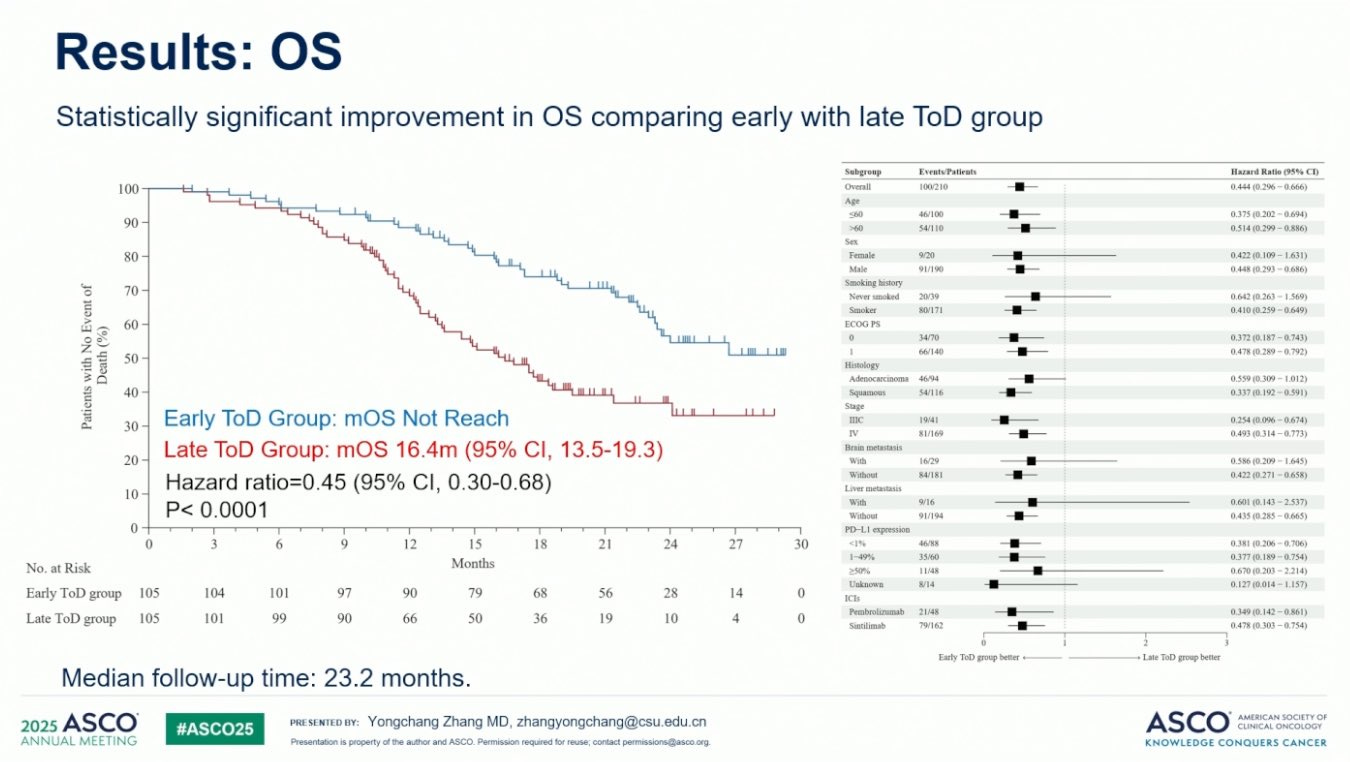

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive the initial four immunochemotherapy cycles before 3p in the early group or after 3p in the late group. 210 patients, 81% with metastatic NSCLC disease were randomized with similar baseline characteristics (per their word). Strikingly, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 13.2 months (95% CI 10.1-16.3) in the early group and 6.5 months (5.9-7.1) in the late group. After a median follow up of 18.9 months, the median overall survival (OS) not reached in the early group but was 17.8 months in the late group (see figure below). The ORR or objective response rate (complete response or partial response rate) was 75% vs. 56% in early versus late group.

They note PFS, OS, and ORR are consistently higher in the early group when adjusted for age, sex, performance status, tumor stage, histology, PD-L1 status, and immunotherapy agent. Hazard ratios (HRs) of PFS for each subgroup they analyzed largely favored the early group but the same was not true for OS.

Notably, females and never smokers have HRs for OS that considerably overlapped one indicating time of day did not matter much for these groups. Also, those with adenocarcinomas have HR for OS that significantly overlapped one or nearly touched one, respectively. Why might this be?

Smoking: Individuals who do not smoke are associated with higher socioeconomic status [Garrett et al 2019; Leventhal et al 2019] . We know socioeconomic status matters for survival outcomes in cancer and can be quite pronounced. Socioeconomic status/financial stress/working jobs that have less flexibility and therefore having to come in later may influence dropout rates in the trial, hours of restorative sleep, baseline strength of their immune system, or even whether a patient accepted enrollment into the trial.

Female vs Male: Immunoaging is more pronounced in males relative to females [Bartz et al 2020, Giefing-Kroll et al 2015, Taneja 2021] . Since females have generally more robust immune systems, they could be relatively insensitive to time of day of immunochemotherapy.

Adeno vs squamous subtype: Chemotherapy regimen recommendations differ for adenocarcinomas and squamous NSCLCs per NCCN guidelines so we may be observing a chemotherapy efficacy difference. It is likely not the primary driver since trials investigating chemotherapy regimens in advanced NSCLC have a PFS/OS effect on the order of a few months, way shorter than observed here.

Put together, these interactions (subtype, socioeconomic status, smoking status, female/male immunoaging differences) if additive may account for much of the difference observed in the results.

Another post a few months ago profiled this conference presentation and had this to say:

But this paper was not a retrospective study of electronic health records, it was a randomized clinical trial, which is the gold standard. This means that we’ll be forced to immediately throw away our list of other obvious complaints against this paper. Yes, healthier patients may come in the morning more often, but randomization fixes that. Yes, patients with better support systems may come in the morning more often, but randomization fixes that. Yes, maybe morning nurses are fresher and more alert, but…well, randomization doesn’t fix evening nurse performance (which does dip during the night!), but I am inclined to believe the errors aren’t so high there as to cause this magnitude of a survival shift.

My counter points to this:

There are a number of randomized trial whose interpretation shifted because of imbalances in baseline populations. ELITE postmenopausal women given estradiol had lower atherosclerotic events compared to placebo BUT they were found to have lower baseline coronary calcium scores. After adjusting for this, effect disappeared. Similar stories for EORTC22921 trial in rectal cancer, and BR.21 in NSCLC. With 210 patients, baseline imbalance could happen. We do not know if socioeconomic status, financial stress, or working fixed hour jobs with limited flexibility for time off are balanced between groups. A subgroup analysis should alleviate that concern.

We see some important subgroups having no benefit in overall survival namely females, and never smokers.

Adjustment for factors using a cox proportional hazards model assumes NON-INFORMATIVE censoring of patients in either arm. There is a lot more censoring especially in the first 12 months in the late group compared to the early group. So, if these patients had to drop out because they needed appointments that better fit their schedules, transporation needs, or other factors tied to socioeconomic status or financial reasons, we may be overestimating the benefit of time-of-day.

Lastly, I wanted to highlight a reason why all of these reasons I outlined before could be wrong. Grade 3+ adverse events were equal between groups including infections; mild leukopenia (grade 1-2) was higher in early time of day group. Despite higher rates of global reduction of white blood cells, after four cycles, CD8+ T cells comprised ~1.2% of peripheral white blood cells in the early group up from 1% at baseline whereas late treated patients had a decline to 0.9% from 1% after four cycles. The ratio of Activated:Exhausted circulating T cells were ~10x higher in the early group relative to late group after four cycles. This points to the possibility that there are more CD8+ T cells capable of killing tumor cells since the number of CD8+ T cells may have remained relatively stable (not completely sure because we do not have absolute count data) and a higher fraction of them were activated. It is unclear at present if these activated CD8+ T cells are able to recognize tumor antigen or penetrate into the tumor microenvironment.

Their inclusion criteria is shown below enrolls patients without detected driver genes in their cell-free DNA taken from venipuncture or tumor biopsy. Roughly 53% of patients with advanced NSCLC have no driver mutation (Ishida et al, 2024) so the treatment benefit to time-of-day would at maximum apply to 47% of advanced NSCLC patients. Thus, the narrowest reading of this conference presentation would be to try to schedule immunotherapy for advanced NSCLC driver negative male patients who smoke and have stable brain metastases before 3p.

If time-of-day matters a lot for immunotherapy, it should be incorporated into standard practice. The logistics and economics of infusion centers should adjust to this. But, before doing so, we need to wait for the randomized trial presented at ASCO to be published so we can look at key subgroups, and have at least one more follow up trial given the implications of cutting infusion center hours.

Personally, I think we do not study non-pharmacologic interventions enough. Examples of these studies include investigating the impact of exercise in colon cancer survival (exercise improves 8 year survival from 83% to 90%) or time-of-day of immunotherapy in lung cancer. In part, these studies are incentivized to not take place because pharmaceutical companies have no reason to do it. They want to fund things that lead to their drug being validated and approved. As Anirban Maitra points out, we need foundations or the government to fund such trials.

Appendix surveying some of the retrospective data on time-of-day impacting outcomes in immunotherapy:

Retrospective mRCC patients with early (before 4:30p) immunotherapy infusion had a median overall survival of 46.3 months compared to 41.7 months for the late infusion group (Dizman et al, 2023). Results were adjusted for age, gender, line of treatment, IMDC risk, and histologic subtype.

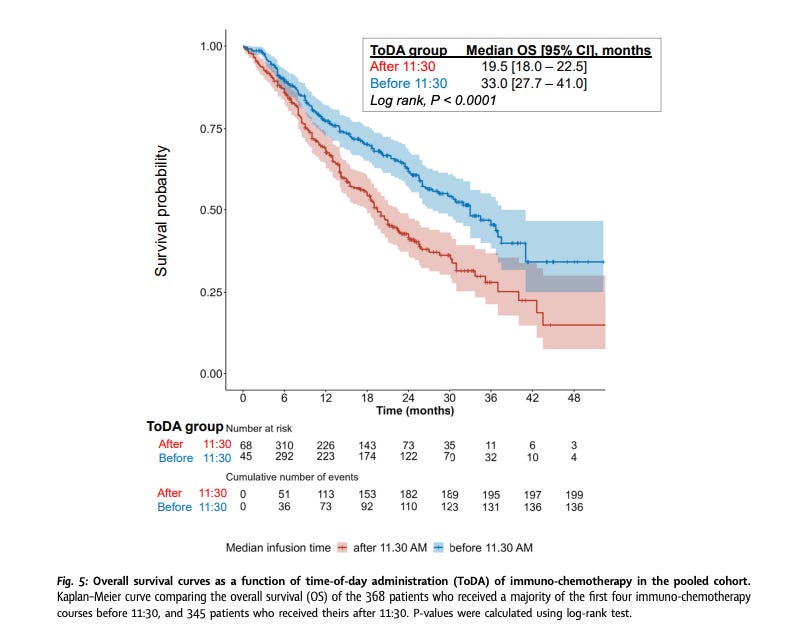

Another retrospective study considered time-of-day that patients stage III or IV non-small cell lung cancer were given immunochemotherapy. Patients who received the majority of their first four infusions before 11:30a had a median overall survival of 33 months compared to 19.5 months for the post-11:30a group. They adjusted for country, sex, age, WHO performance status, tumor stage, PD-L1 expression, number of metastatic sites, type of immunochemotherapy regimen administered. None of the studies I reviewed adjusted for socioeconomic status, financial stress, or lack of transportation.